An alternative source of heat could significantly reduce the carbon footprint of a process which turns food waste into power, new research suggests.

A University of Glasgow-led team of scientists have demonstrated that using air-source heat pumps to support anaerobic digestion could cut the carbon emitted during the production of biogas by more than a third.

Their findings could help support ongoing efforts to decarbonise national electricity grids and enable remote communities to produce their own low-carbon power locally.

Anaerobic digestion uses microorganisms in oxygen-free conditions to break down biodegradable materials like food waste and sewage sludge to release biogas – a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide which can be burned to turn turbines, generating low-carbon electricity.

Machines called bioreactors are used to maintain the optimal temperature during anaerobic digestion to maximise the amount of biogas generated.

The researchers set out to investigate how the carbon footprint of bioreactors heated by air-source heat pumps – which draw ambient heat from the air in a low-carbon process – would compare over the length of their lifetime to conventional heating systems which use boilers powered by natural gas.

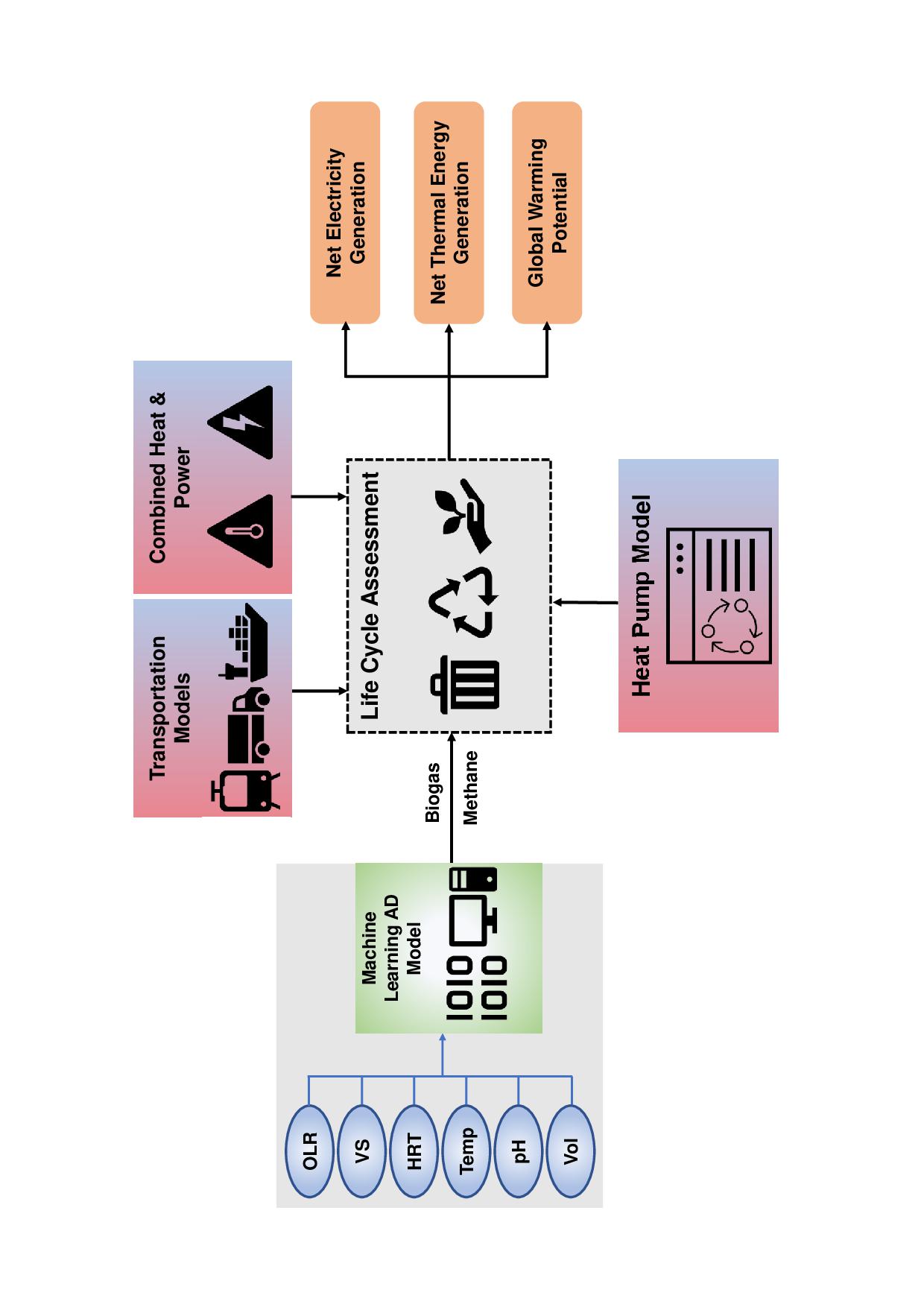

In a new paper, published in the journal Bioresource Technology, the researchers outline how they created a computer model of the thermodynamics of heat pumps. They coupled the model with machine learning-based anaerobic digestion modelling and trained the new system from a database of existing research.

Then, they tested their new model by providing it with previously unseen real-world data to ensure it produced accurate results.

With their model validated, the researchers set about exploring how the carbon footprint of a heat pump-based system would compare to that of a natural gas-based one over the course of their expected lifespans, using a standardised approach called life cycle assessment.

They found that the heat pump system would emit significantly less carbon than the baseline natural gas system when used to process food waste and sewage sludge.

The modelled carbon reduction was up to 28.1% in an anaerobic digestion process maintained at a temperature of 55°C. At a lower temperature of 37.5°C, the carbon footprint of the process was reduced even further to a maximum of 36.1%.

Dr Siming You, from the University of Glasgow’s James Watt School of Engineering, is the paper’s corresponding author. He said: “Humans unavoidably produce biodegradable waste on scales from the very small, like the scrapings from a dinner plate, to the very large, like urban wastewater treatment plants.

“All of this waste releases gas when it decays, some of which can be harmful to the environment. By harnessing that gas as a source for power production instead of letting it decay naturally, we can take strides towards the circular, net-zero economy that we urgently need to build to reduce the impact of climate change.

“This model is the first technical and environmental assessment of just how useful air-source heat pumps could be in decarbonising the process of producing biogas. The results suggest that there’s a significant role for heat pumps in supporting low-carbon anaerobic digestion.

“That could help inform future planning for municipal waste management facilities to help reduce their carbon footprints. It could also underpin the development of future bioreactors which could be used in remote communities to help people turn their waste into biogas.

“That kind of decentralised waste recycling could go a long way to helping people produce their own local source of electricity. The research is also part of a larger effort to decarbonise water and wastewater treatment in rural communities.”

Researchers from the University of Glasgow and University College London contributed to the paper, which is titled ‘Integration of Anaerobic Digestion with Heat Pump: Machine Learning-based Technical and Environmental Assessment’. It is published in Bioresource Technology.

The research was supported by funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), the Supergen Bioenergy Hub and the Royal Society.